B-29 CREWS TORTURED BY THE JAPANESE

Japanese war crimes

I am completely speechless, disgusted, saddened, shocked, infuriated, and sick after researching this story about JAPANESE WAR ATROCITIES. If you can read this article without being shocked to the point of throwing up, then you must have a strong stomach. As time passes we deny the Holocaust, and the Japanese make continued long term attempts to re-write history. I hope to GOD that a few of us will know first hand what brutality the Japanese did to our prisoners. This article is the absolute most complete, authoritative documentary on Japanese brutality. Our prisoners were used by vivisectionist to tortures that are heartbreaking. They performed operations, removing arms and legs from living man. Each day meat was cut from them and fed to the Japanese troops. Rape was rampant, there were amputations, castrations, mass killings, biological experiments, and of course the favorite Japanese atrocity, the beheading. The cannibalism, forced labor, chemical experimentation, looting, and mutilation of women are some of the sick crimes committed by the Japanese.

This is only part one in a series of three articles covering these atrocities. Part two covers the BATAAN DEATH MARCH, and part three covers the NANKING MASSACRE. These are only three of the hundreds of similar incidents. If you care anything about History, or the culture of the Japanese race, it will be worth your time to read and absorb these articles

WEBSITE HISTORIAN

Japanese war crimes occurred during the period of Japanese imperialism. Other names, such as the Asian Holocaust and Japanese war atrocities, are also used for these events. Some war crimes were committed by military personnel from the Empire of Japan in the late 19th century, although most took place during the first part of the Showa Era, until the defeat of Japan in 1945. Historians and governments of many countries officially hold Japanese military forces, namely the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy, responsible for killings and other crimes committed against many millions of civilians and prisoners of war (POWs).

Definitions

War crimes may be broadly defined as unconscionable behavior by a government or military personnel against either enemy civilians or enemy combatants. Military personnel from the Empire of Japan have been accused and/or convicted of committing many such acts during the period of Japanese imperialism from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. They have been accused of conducting a series of human rights abuses against civilians and prisoners of war (POWs) throughout east Asia and the western Pacific region. These events reached their height during the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45 and the Asian and Pacific campaigns of World War II (1941-45)

International and Japanese law

Although the Empire of Japan did not sign the Geneva Conventions, which have provided the standard definition of war crimes since 1864, the crimes committed fall under other aspects of international and Japanese law. For example, many of the alleged crimes committed by Japanese personnel broke Japanese military law, and were not subject to court martial, as required by that law. The Empire also violated international agreements signed by Japan, including provisions of the Treaty of Versailles such as a ban on the use of chemical weapons, and the Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907), which protect prisoners of war (POWs). The Japanese government also signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1929), thereby rendering its actions in 1937-45 liable to charges of crimes against peace, a charge that was introduced at the Tokyo Trials to prosecute “Class A” war criminals. “Class B” war criminals were those found guilty of war crimes per se, and “Class C” war criminals were those guilty of crimes against humanity. The Japanese government also accepted the terms set by the Potsdam Declaration (1945) after the end of the war. The declaration alluded, in Article 10, to two kinds of war crime: one was the violation of international laws, such as the abuse of prisoners of war; the other was obstructing “democratic tendencies among the Japanese people” and civil liberties within Japan.

In Japan, the term “Japanese war crimes” generally only refers to cases tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, also known as the Tokyo Trials, following the end of the Pacific War. However, the tribunal did not prosecute war crimes allegations involving mid-ranking officers or more junior personnel. Those were dealt with separately in other cities throughout the Asia-Pacific region.

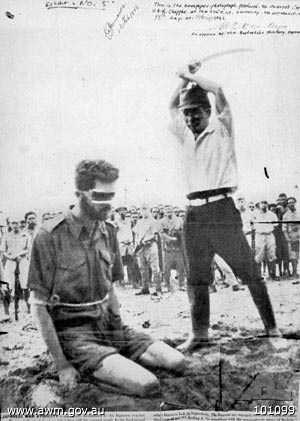

An Australian soldier, Sgt. Leonard Siffleet, about to be beheaded with a katana sword

Aitape, New Guinea, 1943. An Australian soldier, Sgt Leonard Siffleet, about to be beheaded with a katana sword. Many Allied prisoners of war were summarily executed by Japanese forces during the Pacific War.

Japanese law does not define those convicted in the post-1945 trials as criminals, despite the fact that Japan’s governments have accepted the judgments made in the trials, and in the Treaty of San Francisco (1952). This is because the treaty does not mention the legal validity of the tribunal. Had Japan certified the legal validity of the war crimes tribunals in the San Francisco Treaty, the war crimes would have became open to appeal and overturning in Japanese courts. This would have been unacceptable in international diplomatic circles. The current Japanese jurists’ consensus regarding the legal standing of the Tokyo tribunal is that the execution and/or incarceration of an individual as result of the post-war trials is valid, but has no relationship to Japanese criminal law.

Historical and geographical extent

Outside Japan, different societies use widely different timeframes in defining Japanese war crimes. For example, the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910 was followed by the deprivation of civil liberties and exploitations against the Korean people. Thus, some Koreans refer to “Japanese war crimes” as events occurring during the period of 1910 (or earlier) to 1945.

By comparison, the Western Allies did not come into military conflict with Japan until 1941, and North Americans, Australasians, South East Asians and Europeans may consider “Japanese war crimes” to be events that occurred in 1941-45.

Japanese war crimes were not always carried out by ethnic Japanese personnel. A small minority of people in every Asian and Pacific country invaded and/or occupied by Japan collaborated with the Japanese military, or even served in it, for a wide variety of reasons, such as economic hardship, coercion, or antipathy to other imperialist powers.

Japan’s sovereignty over Korea and Formosa, in the first half of the 20th century, was recognized by international agreements the Treaty of Shimonoseki (1895) and the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty (1910) and they were considered at the time to be integral parts of the Japanese Empire. However, the legality of these treaties is in question, the native populations were not consulted, there was armed resistance to Japan’s annexations, and war crimes may also be committed during civil wars.

Background

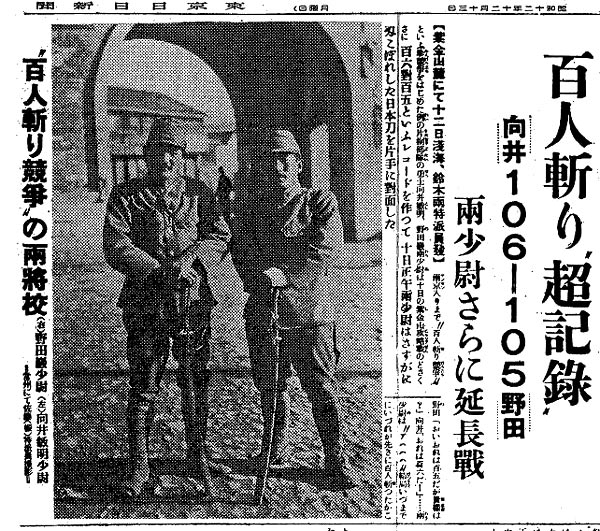

Two Japanese Officers in a contest to see who could kill 100 people first.

Two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda competing to see who could kill (with a sword) one hundred people first. The bold headline reads,

” ‘Incredible Record’ (in the Contest To Cut Down 100 People – Mukai 106 – 105 Noda – Both 2nd Lieutenants Go Into Extra Innings”

Japanese military culture and imperialism

Military culture, especially during Japan’s imperialist phase had great bearing on the conduct of the Japanese military before and during World War II.

Centuries previously, the samurai of Japan had been taught unquestioning obedience to their lords, as well as to be fearless in battle. After the Meiji Restoration and the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the Emperor became the focus of military loyalty. During the so-called “Age of Empire” in the late 19th century, Japan followed the lead of other world powers in developing an empire, pursuing that objective aggressively.

As with other imperial powers, Japanese popular culture became increasingly jingoistic through the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century. The rise of Japanese nationalism was seen partly in the adoption of Shinto as a state religion from 1890, including its entrenchment in the education system. Shinto held the Emperor to be divine because he was deemed to be a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu. This provided justification for the requirement that the emperor and his representatives be obeyed without question.

Victory in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) signified Japan’s rise to the status of a world power. Unlike the other major powers, Japan did not sign the Geneva Convention which stipulates the humane treatment of civilians and POWs until after World War II. Nevertheless, the treatment of prisoners by the Japanese military in wars such as the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) and World War I (1914-18), was at least as humane as that of other militaries.

The events of the 1930s and 1940s

By the late 1930s, the rise of militarism in Japan created at least superficial similarities between the wider Japanese military culture and that of Nazi Germany’s elite military personnel, such as those in the Waffen-SS. Japan also had a military secret police force, known as the Kempeitai, which resembled the Nazi Gestapo in its role in annexed and occupied countries.

As in other dictatorships, irrational brutality, hatred and fear became commonplace. Perceived failure, or insufficient devotion to the Emperor would attract punishment, frequently of the physical kind. In the military, officers would assault and beat men under their command, who would pass the beating on to lower ranks, all the way down. In POW camps, this meant prisoners received the worst beatings of all.

The crimes

Because of the sheer scale of suffering caused by the Japanese military during the 1930s and 1940s, it is often compared to the military of Nazi Germany during 1933-45. The historian Chalmers Johnson has written that:

It may be pointless to try to establish which World War Two Axis aggressor, Germany or Japan, was the more brutal to the peoples it victimized. The Germans killed six million Jews and 20 million Russians [i.e. Soviet citizens]; the Japanese slaughtered as many as 30 million Filipinos, Malays, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Indonesians and Burmese, at least 23 million of them ethnic Chinese. Both nations looted the countries they conquered on a monumental scale, though Japan plundered more, over a longer period, than the Nazis. Both conquerors enslaved millions and exploited them as forced laborer’s and, in the case of the Japanese, as forced prostitutes for front-line troops. If you were a Nazi prisoner of war from Britain, America, Australia, New Zealand or Canada (but not Russia) you faced a 4 % chance of not surviving the war; by comparison the death rate for Allied POWs held by the Japanese was nearly 30 %.

Mass killings

R. J. Rummel, a professor of political science at the University of Hawaii, states that between 1937 and 1945, the Japanese military “murdered near 3,000,000 to over 10,000,000 people, most probably 6,000,000 Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and Indochinese, among others, including Western prisoners of war. This democide was due to a morally bankrupt political and military strategy, military expediency and custom, and national culture.” Among the most infamous incidents in Southeast Asia were the Manila massacre, which resulted in the deaths of 100,000 civilians in the Phillipines and the Sook Ching massacre, in which between 25,000 and 50,000 ethnic Chinese in Singapore were taken to beaches and massacred.

In China alone, during 1937-45, approximately 3.9 million Chinese were killed, mostly civilians as a direct result of the Japanese invasion. The most infamous incident during this period was the Nanjing Massacre of 1937-38, when, according to the findings of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, the Japanese Army massacred as many as 260,000 civilians and prisoners of war. Herbert Bix, citing the works of Mitsuyoshi Himeta and Akira Fujiwara, claims that the “Three Alls Policy” (Sanko Sakusen) a scorched earth strategy used by Japanese forces in China in 1942-45, and sanctioned by Hirohito himself, was in itself responsible for the deaths of 2.7 million Chinese civilians. The mystery behind Hirohito’s role is explained in the authoritative book by David Bergamini, who translated war diaries and depositions from the tribunals from the original Japanese, and interviewed sources directly. Similar crimes such as Changjiao massacre did occur from time to time.

Experiments on humans and biological warfare

Special Japanese military units conducted experiments on civilians and POWs in China. One of the most infamous was Unit 731. Victims were subjected to vivisection without anesthesia, amputations, and were used to test biological weapons, among other experiments. Anesthesia was not used because it was considered to affect results. In some victims, animal blood was injected into their bodies.

To determine the treatment of frostbite, prisoners were taken outside in freezing weather and left with exposed arms, periodically drenched with water until frozen solid. The arm was later amputated; the doctor would repeat the process on the victim’s upper arm to the shoulder. After both arms were gone, the doctors moved on to the legs until only a head and torso remained. The victim was then used for plague and pathogens experiments.

According to GlobalSecurity.org, the experiments carried out by Unit 731 alone caused 3,000 deaths. Furthermore, “tens of thousands, and perhaps as many 200,000, Chinese died of bubonic plague, cholera, anthrax and other diseases…”, resulting from the use of biological warfare.

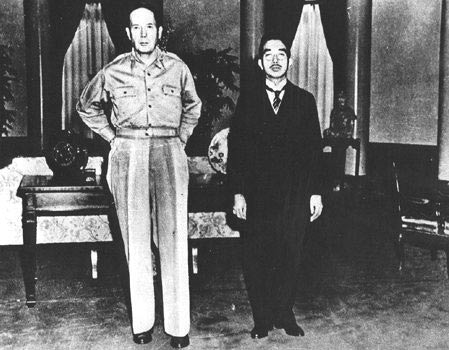

One of the most notorious cases of human experimentation occurred in Japan itself. At least nine out of 12 crew members survived the crash of a U.S. Army Air Forces B-29 bomber on Kyushu, on May 5, 1945. The bomber’s commander was sent to Tokyo for interrogation, while the other survivors were taken to the anatomy department of Kyushu University, at Fukuoka, where they were subjected to vivisection and/or killed. On March 11, 1948, 30 people including several doctors were brought to trial by the Allied war crimes tribunal. Charges of cannibalism were dropped, but 23 people were found guilty of vivisection and/or wrongful removal of body parts. Five were sentenced to death, four to life imprisonment, and the rest to shorter terms. In 1950, the military governor of Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, commuted all of the death sentences and significantly reduced most of the prison terms. All of those convicted in relation to the university vivisection were free by 1958.

In 2006, former IJN medical officer Akira Makino stated that he was ordered as part of his training to carry out vivisection on about 30 civilian prisoners in The Philippines between December 1944 and February 1945. The surgery included amputations and the victims included women and children.

Use of chemical weapons

According to historians Yoshiaki Yoshimi and Seiya Matsuno, Emperor Hirohito authorized by specific orders the use of chemical weapons in China. For example, during the invasion of Wuhan from August to October 1938, the Emperor authorized the use of toxic gas on 375 separate occasions, despite Article 171 of the Versailles Peace Treaty and a resolution adopted by the League of Nations on May 14, condemning the use of poison gas by Japan.

Preventable famine

Deaths caused by the diversion of resources to the Japanese military in occupied countries are also regarded as war crimes by many people. Millions of civilians in southern Asia especially Vietnam and the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia), both of which were major rice-growing countries died during a preventable famine in 1944-45.

Torture of POWs

Japanese imperial forces are also reported to have utilized widespread use of torture on prisoners, usually in an effort to gather military intelligence quickly. Tortured prisoners were often later executed. A former Japanese Army officer who served in China, Uno Shintaro, stated:

The major means of getting intelligence was to extract information by interrogating prisoners. Torture was an unavoidable necessity. Murdering and burying them follows naturally. You do it so you won’t be found out. I believed and acted this way because I was convinced of what I was doing. We carried out our duty as instructed by our masters. We did it for the sake of our country. From our filial obligation to our ancestors. On the battlefield, we never really considered the Chinese humans. When you’re winning, the losers look really miserable. We concluded that the Yamato [i.e. Japanese] race was superior.

After the war, a total of 25 individuals were indicted as “Class A” war criminals, and 5,700 individuals were indicted as “Class B” or “Class C” war criminals by Allied criminal trials. This number included 178 ethnic Taiwanese and 148 ethnic Koreans. Of these, 984 were initially condemned to death, 920 were actually executed, 475 received life sentences, 2,944 received some prison terms, 1,018 were acquitted, and 279 were not sentenced or not brought to trial. High ranking executed individuals included Hideki Tojo, Tomoyuki Yamashita, and Masaharu Homma. The most prominent ethnic Korean was Lieutenant General Hong Sa Ik, who orchestrated the organization of prisoner of war camps in Southeast Asia. In 2006, the South Korean government pardoned 83 of the 148 convicted Korean war criminals.

Cannibalism

Many written reports and testimonies collected by the Australian War Crimes Section of the Tokyo tribunal, and investigated by prosecutor William Webb (the future Judge-in-Chief), indicate that Japanese personnel in many parts of Asia and the Pacific committed acts of cannibalism against Allied prisoners of war. In many cases this was inspired by ever-increasing Allied attacks on Japanese supply lines, and the death and illness of Japanese personnel as a result of hunger. However, according to historian Yuki Tanaka: “cannibalism was often a systematic activity conducted by whole squads and under the command of officers”. This frequently involved murder for the purpose of securing bodies. For example, an Indian POW, Havildar Changdi Ram, testified that: ” on November 12, 1944 the Kempeitai beheaded an Allied pilot. I saw this from behind a tree and watched some of the Japanese cut flesh from his arms, legs, hips, buttocks and carry it off to their quarters… They cut it small pieces and fried it.”

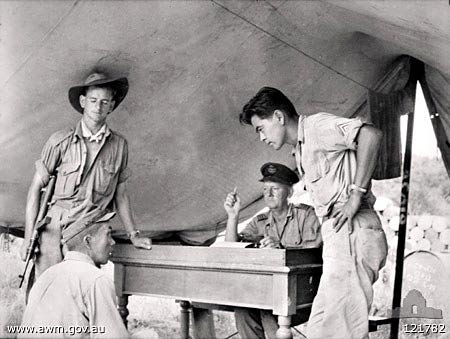

November 9, 1945. Jemadar (junior commissioned officer) Chint Singh of the Indian Army at an identification parade in New Guinea, indicating a Japanese soldier whom Singh claimed had mistreated him, while he was a prisoner of war. Japanese forces used many Indian Army personnel captured in Malaya and Singapore, as forced labor in the South West Pacific.

In some cases, flesh was cut from living people: another Indian POW, Lance Naik Hatam Ali (later a citizen of Pakistan), testified that in New Guinea:

the Japanese started selecting prisoners and everyday one prisoner was taken out and killed and eaten by the soldiers. I personally saw this happen and about 100 prisoners were eaten at this place by the Japanese. The remainder of us were taken to another spot 50 miles [80 km] away where 10 prisoners died of sickness. At this place, the Japanese again started selecting prisoners to eat. Those selected were taken to a hut where their flesh was cut from their bodies while they were alive and they were thrown into a ditch where they later died.

Perhaps the most senior officer convicted of cannibalism was Lt Gen. Yoshio Tachibana, who with 11 other Japanese personnel was tried in relation to the execution of U.S. Navy airmen, and the cannibalism of at least one of them, in August 1944, on Chichi Jima, in the Bonin Islands. They were beheaded on Tachibana’s orders. As military and international law did not specifically deal with cannibalism, they were tried for murder and “prevention of honorable burial”. Tachibana was sentenced to death.

Forced labor

The Japanese military’s use of forced labor, by Asian civilians and POWs also caused many deaths. According to a joint study by historians including Zhifen Ju, Mitsuyoshi Himeta, Toru Kubo and Mark Peattie, more than 10 million Chinese civilians were mobilized by the Ka-in (Japanese Asia Development Board) for forced labor. More than 100,000 civilians and POWs died in the construction of the Burma-Siam Railway.

The U.S. Library of Congress estimates that in Java, between four and 10 million romusha (Japanese: “manual laborer”), were forced to work by the Japanese military. About 270,000 of these Javanese laborers were sent to other Japanese-held areas in South East Asia. Only 52,000 were repatriated to Java, meaning that there was a death rate of 80%.

The Geneva Convention exempted POWs of sergeant rank or higher from manual labor, and stipulated that prisoners performing work should be provided with extra rations and other essentials. According to historian Akira Fujiwara, Emperor Hirohito personally ratified the decision to remove the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners of war in the directive of 5 August 1937. This notification also advised staff officers to stop using the term “prisoners of war”. During World War II, such rules were largely respected in German POW camps, except in the case of Soviet POWs. However, Japan was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention at the time, and Japanese forces did not follow the convention.

Comfort women

The term comfort women (or military comfort women was a euphemism for women in Japanese military brothels in occupied countries, many of whom were recruited by force or deception and regard themselves as having been sex slaves. The extent to which individuals were forced to become comfort women has been disputed. Some sources claim that virtually all comfort women consented to becoming prostitutes and/or were paid, but others have presented research establishing a link between the Japanese military and the forced recruitment of local women.

In 1992, historian Yoshiaki Yoshimi published material based on his research in archives at the National Institute for Defense Studies. Yoshimi claimed that there was a direct link between imperial institutions such as the Ka-in and “comfort stations”. When Yoshimi’s findings were published in the Japanese media on January 12, 1993 they caused a sensation and forced the government, represented by the Chief Cabinet Secretary, Kato Koichi, to acknowledge some of the facts that same day. On January 17, Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa presented formal apologies for the suffering of the victims, during a trip in South Korea. On July 6 and August 4, the Japanese government issued two statements by which it recognized that “Comfort stations were operated in response to the request of the military of the day”, “The Japanese military was, directly or indirectly, involved in the establishment and management of the comfort stations and the transfer of comfort women” and that the women were “recruited in many cases against their own will through coaxing and coercion”.

On March 1, 2007, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe mentioned suggestions that a U.S. House of Representatives committee would call on the Japanese Government to “apologize for and acknowledge” the role of the Japanese Imperial military in wartime sex slavery. However, Abe denied that it applied to comfort stations. “There is no evidence to prove there was coercion, nothing to support it.”

However, it provoked negative reaction from Asian and Western countries, for example, The New York Times editorial on March 6, these were not commercial brothels. Force, explicit and implicit, was used in recruiting these women. What went on in them was serial rape, not prostitution. The Japanese Army’s involvement is documented in the government’s own defense files. A senior Tokyo official more or less apologized for this horrific crime in 1993. Yesterday, he grudgingly acknowledged the 1993 quasi apology, but only as part of a pre-emptive declaration that his government would reject the call, now pending in the United States Congress, for an official apology. America isn’t the only country interested in seeing Japan belatedly accept full responsibility. Korea and China are also infuriated by years of Japanese equivocations over the issue.

The same day, veteran soldier Yasuji Kaneko admitted to The Washington Post that the women “cried out, but it didn’t matter to us whether the women lived or died. We were the emperor’s soldiers. Whether in military brothels or in the villages, we raped without reluctance.”

A Dutch-Indonesian “comfort woman”, Jan Ruff-O’Hearn, who gave evidence to the U.S. committee, said the Japanese Government had failed to take responsibility for its crimes, that it did not want to pay compensation to victims and that it wanted to rewrite history. Ruff-O’Hearn said that she had been raped “day and night” for three months by Japanese soldiers when she was 21.

There are different theories on the breakdown of the comfort women’s place of origin. While some sources claim that the majority of the women were from Japan, others, including Yoshimi, argue as many as 200,000 women, mostly from Korea and China, and some other countries such as the Philippines, Taiwan, Burma, Netherlands, Australia and the Dutch East Indies were forced to engage in sexual activity.

Looting

General Tomoyuki Yamashita (second right) was responsible for hiding the loot known as Yamashita’s gold. He was tried in Manila between October 29 and December 7, 1945, by a U.S. military commission, on charges relating to the Manila Massacre and earlier occurrences in Singapore, and was sentenced to death. The case set a precedent regarding the responsibility of commanders for war crimes, and is known as the Yamashita Standard. The legitimacy of the hasty trial has been called into question.

Many historians state that violence by Japanese personnel was closely tied to looting. For example, Sterling and Peggy Seagrave, in a 2003 book on “Yamashita’s Gold” secret repositories of loot from across Southeast Asia, in the Philippines argued that the theft was organized on a massive scale, either by yakuza gangsters such as Yoshio Kodama, or by officials at the behest of Emperor Hirohito, who wanted to ensure that as many of the proceeds as possible went to the government. The Seagraves allege that Hirohito appointed his brother, Prince Chichibu, to head a secret organization called Kin no yuri (Golden Lily) for this purpose.

Post-1945 reactions

The Tokyo Trials

The Tokyo Trials, which were conducted by the Allied powers, found many people guilty of such crimes, including three former (unelected) prime ministers: Koki Hirota, Hideki Tojo, and Kuniaki Koiso. Many military leaders were also convicted. Two people convicted as Class-A war criminals later served as ministers in post-war Japanese governments.

- Mamoru Shigemitsu served as foreign minister both during the war and in the post-war Hatoyama government.

- Okinori Kaya was finance minister during the war and later served as justice minister in the government of Hayato Ikeda. However, these two had no direct connection to alleged war crimes committed by Japanese forces, and foreign governments never raised the issue when they were appointed.

Emperor Showa and all members of the imperial family implicated in the war such as prince Chichibu, prince Asaka, prince Takeda and prince Higashikuni were exonerated from criminal prosecutions by Douglas MacArthur. Many historians criticize this decision. According to John Dower, even Japanese activists who endorse the ideals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo charters, and who have labored to document and publicize the atrocities of the showa regime “cannot defend the American decision to exonerate the emperor of war responsibility and then, in the chill of the Cold war, release and soon afterwards openly embrace accused right-winged war criminals like the later prime minister Nobusuke Kishi.” For Herbert Bix, “MacArthur’s truly extraordinary measures to save Hirohito from trial as a war criminal had a lasting and profoundly distorting impact on Japanese understanding of the lost war.”

Other trials

October 26, 1945, Sandakan, North Borneo. During the investigation into Sandakan Death Marches and other incidents, Sergeant Hosotani Naoji (left, seated), a member of the Kempeitai unit at Sandakan, is interrogated by Squadron Leader F. G. Birchall (second right) of the Royal Australian Air Force, and Sergeant Mamo (right), a Nisei member of the U.S. Army/Allied Translator and Interpreter Service. Naoji confessed to shooting two Australian POWs and five ethnic Chinese civilians.

Besides the Tokyo Trials, other prosecutions of Japanese personnel for war crimes were also held in many other cities throughout Asia and the Pacific, during 1946-51. Some 5,600 Japanese personnel were prosecuted in more than 2,200 trials. The judges presiding came from the United States, China, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands, France, the Soviet Union, New Zealand, India and the Philippines. More than 4,400 Japanese personnel were convicted and about 1,000 were sentenced to death. The largest single trial was that of 93 Japanese personnel charged with the summary execution of more than 300 Allied POWs, in the Laha massacre (1942).

Official apologies

The Japanese government considers that the legal and moral positions in regard to war crimes are separate. Therefore, while maintaining that Japan violated no international law or treaties, Japanese governments have officially recognized the suffering which the Japanese military caused, and numerous apologies have been issued by the Japanese government. For example, Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama, in August 1995, stated that Japan “through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations”, and he expressed his “feelings of deep remorse” and stated his “heartfelt apology”. Also, on September 29, 1972, Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka stated, “The Japanese side is keenly conscious of the responsibility for the serious damage that Japan caused in the past to the Chinese people through war, and deeply reproaches itself.”

However, the official apologies are widely viewed as inadequate by many of the survivors of such crimes and/or the families of dead victims. The subject of official apologies is controversial as many people aggrieved by alleged Japanese war crimes maintain that no apology has been issued for particular acts and/or that the Japanese government has merely expressed “regret” or “remorse”. On 2 March 2007, the issue was raised again by Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, in which he denied that the military had forced women into sexual slavery during World War II. He stated, “The fact is, there is no evidence to prove there was coercion.” Before he spoke, a group of Liberal Democratic Party lawmakers also sought to revise Yohei Kono’s 1993 apology to former comfort women.

However, it provoked negative reaction from Asian and Western countries, for example, The New York Times editorial on March 6, these were not commercial brothels. Force, explicit and implicit, was used in recruiting these women. What went on in them was serial rape, not prostitution. The Japanese Army’s involvement is documented in the government’s own defense files. A senior Tokyo official more or less apologized for this horrific crime in 1993. Yesterday, he grudgingly acknowledged the 1993 quasi apology, but only as part of a pre-emptive declaration that his government would reject the call, now pending in the United States Congress, for an official apology. America isn’t the only country interested in seeing Japan belatedly accept full responsibility. Korea and China are also infuriated by years of Japanese equivocations over the issue.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, an apology is “a formal, public statement of regret”, and moreover, the Japanese word for “apology” itself has also been used on several occasions. Some allege that the media in some countries “glosses over” or hides efforts at reconciliation by Japan, including “generous” Japanese aid packages, especially in countries where media outlets are under formal or de facto state control. It is further alleged that this reflects anti-Japanese sentiment.

German Nazis propaganda also justified their persecution of the Jewish people on the paranoic ground that the Jewish constantly oppressed and extorted Germans fermenting anti-German sentiment.

Some in Japan have asserted that what is being demanded is that the Japanese Prime Minister and/or the Emperor perform dogeza, in which an individual kneels and bows his head to the ground a high form of apology in east Asian societies that Japan appears unwilling to do.

Some point to an act by German Chancellor Willy Brandt, who knelt at a monument to the Jewish victims of the Warsaw Ghetto, in 1970, as an example of a powerful and effective act of apology and reconciliation, although not everyone agrees.

Citing Brandt’s action as an example, John Borneman, associate professor of anthropology at Cornell, states that, “an apology represents a non-material or purely symbolic exchange whereby the wrongdoer voluntarily lowers his own status as a person.” Borneman further states that once this type of apology is given, the injured party must forgive and seek reconciliation, or else the apology won’t have any effect. The injured party may reject the apology for several reasons, one of which is to prevent reconciliation, because, “By keeping the memory of the wound alive, refusals prevent an affirmation of mutual humanity by instrumentalizing the power embedded in the status of a permanent victim.”

Therefore, some argue that a nation’s reluctance to accept the conciliatory gestures that Japan has made may be because that nation doesn’t think that Japan has “lowered” itself enough to provide a sincere apology. On the other hand, others state their belief that that particular nation is choosing to reject reconciliation in pursuit of permanent “victimhood” status as a way to try to assert power over Japan.

Compensation

There is a widespread perception that the Japanese government has not accepted the legal responsibility for compensation and, as a direct consequence of this denial, it has failed to compensate the individual victims of Japanese atrocities. In particular, a number of prominent human rights and women’s rights organizations insist that Japan still has a moral and/or legal responsibility to compensate individual victims, especially the sex slaves conscripted by the Japanese military in occupied countries and known as comfort women.

The Japanese government officially accepted the requirement for monetary compensation to victims of war crimes, as specified by the Potsdam Declaration. The details of this compensation have been left to bilateral treaties with individual countries, except North Korea, because Japan recognizes South Korea as the sole legitimate government of the Korean peninsula. In the case of POWs from the western Allies, compensation was paid to the victims through the Red Cross. The total amount Japan paid was 4,500,000. However, in a number of Asian countries, claims for compensation were either: abandoned for political reasons, or; paid by Japan, under the specific understanding that it would be used for individual compensation, but was not paid out to the victims by the governments concerned. Therefore a large number of individual victims in Asia received no compensation.

Therefore, the Japanese government’s position is that the proper avenues for further claims are the governments of the respective claimants. As a result, every individual compensation claim brought to Japanese court has failed. Such was the case in regard to a British POW who was unsuccessful in an attempt to sue the Japanese government for additional money for compensation. As a result, the UK Government later paid additional compensation to all British POWs. There were complaints in Japan that the international media simply stated that the former POW was demanding compensation and failed to clarify that he was seeking further compensation, in addition to that paid previously by the Japanese government.

A small number of claims have also been brought in US courts, though these have also been rejected.

During the treaty negotiation with South Korea, the Japanese government proposed that it pay monetary compensation to individual Korean victims, in line with the payments to western POWs. The Korean government instead insisted that Japan pay money collectively to the Korean government. The contents of negotiations had been veiled for 40 years until the Korean public demanded its release. Against opposition of Japanese government, 1,200 pages of diplomatic documents produced prior to Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea became public in 2005.

There are those that insist that because the governments of China and Taiwan abandoned their claims for monetary compensation, then the moral and/or legal responsibility for compensation belongs with these governments. Such critics also point out that even though these governments abandoned their claims, they signed treaties that recognized the transfer of Japanese colonial assets to the respective governments. Therefore, to claim that these governments received no compensation from Japan is incorrect, and they could have compensated individual victims from the proceeds of such transfers. However, others dispute that Japanese colonial assets in large proportion were built or stolen with extortion or force in occupied countries as artworks collected (or stolen) by Nazis during WWII throughout Europe.

The Japanese government, while admitting no legal responsibility for the so-called “comfort women”, set up the Asian Women’s Fund in 1995, which gives money to people who claim to have been forced into prostitution during the war. Though the organization was established by the government, legally, it has been created such that it is an independent charity. The activities of the fund have been controversial in Japan, as well as with international organizations supporting the women concerned. Some argue that such a fund is part of an ongoing refusal by the Japanese government to face up to its responsibilities, while others say that the Japanese government has long since finalized its responsibility to individual victims and is merely correcting the failures of the victims’ own governments.

The reality is that without a sincere and unequivocal apology from the government of Japan, the majority of surviving Comfort Women refused to accept these funds.

Intermediate compensation

The term “intermediate compensation” (or intermediary compensation) was applied to the removal and reallocation of Japanese industrial (particularly military-industrial) assets to Allied countries. It was conducted under the supervision of Allied occupation forces. This reallocation was referred to as “intermediate” because it did not amount to a final settlement by means of bilateral treaties, which settled all existing issues of compensation. By 1950, the assets reallocated amounted to 43,918 items of machinery, valued at 165,158,839 (in 1950 prices). The proportions in which the assets were distributed were: China, 54.1%; the Netherlands, 11.5%; the Philippines 19%, and; the United Kingdom, 15.4%.

The last payment was made to the Philippines on July 22, 1976.

Debate in Japan

There is a widespread perception, outside Japan, that there is a reluctance inside Japan to discuss such events and/or admit that there were war crimes. However, the controversial events of the Japanese imperial era are openly debated in the media, with the various political parties and ideological groups taking quite different positions. What differentiates Japan from Germany and Austria is that in Japan, there is no restriction to the freedom of speech in regard to this matter, while in Germany, Austria and some other European countries, Holocaust denial is a criminal offence.

Until the 1970s, such debates were considered a fringe topic in the media. In the Japanese media, the opinions of the political center and left tends to dominate the editorials of newspapers, while the right tend to dominate magazines. Debates regarding war crimes were confined largely to the editorials of tabloid magazines where calls for the overthrow of “Imperialist America” and revived veneration of the Emperor coexisted with pornography. In 1972, to commemorate the normalization of relationship with China, Asahi Shimbun, a major liberal newspaper, ran a series on Japanese war crimes in China including the Nanking Massacre. This opened the floodgates to debates which have continued ever since. The 1990s are generally considered to be the period in which such issues become truly mainstream, and incidents such as the Nanking Massacre, Yasukuni Shrine, comfort women, the accuracy of school history textbooks, and the validity of the Tokyo Trials were debated, even on television.

As the consensus of Japanese jurists is that Japanese forces did not technically commit violations of international law, many right wing elements in Japan have taken this to mean that war crimes trials were examples of victor’s justice. They see those convicted of war crimes as “Martyrs of Showa”, Showa being the name given to the rule of Hirohito. This interpretation is vigorously contested by Japanese peace groups and the political left. In the past, these groups have tended to argue that the trials hold some validity, either under the Geneva Convention (even though Japan hadn’t signed it), or under an undefined concept of international law or consensus. Alternatively, they have argued that, although the trials may not have been technically valid, they were still just, somewhat in line with popular opinion in the West and in the rest of Asia.

By the early 21st century, the revived interest in Japan’s imperial past had brought new interpretations from a group which has been labelled both “new right” and “new left”. This group points out that many acts committed by Japanese forces, including the Nanjing Incident (they generally do not use the word “massacre”), were violations of the Japanese military code. It is suggested that had war crimes tribunals been conducted by the post-war Japanese government, in strict accordance with Japanese military law, many of those who were accused would still have been convicted and executed. Therefore, the moral and legal failures in question were the fault of the Japanese military and the government, for not executing their constitutionally-defined duty.

The new right/new left also takes the view that the Allies committed no war crimes against Japan, because Japan was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention, and as a victors, the Allies had every right to demand some form of retribution, to which Japan consented in various treaties.

However, under the same logic, the new right/new left considers the killing of Chinese who were suspected of guerilla activity to be perfectly legal and valid, including some of those killed at Nanjing, for example. They also take the view that many Chinese civilian casualties resulted from the scorched earth tactics of the Chinese nationalists. Though such tactics are arguably legal, the new right/new left takes the position that some of the civilian deaths caused by these scorched earth tactics are wrongly attributed to the Japanese military.

Similarly, they take the position that those who have attempted to sue the Japanese government for compensation have no legal and/or moral case.

The new right/new left also takes a less sympathetic view of Korean claims of victimhood, because prior to annexation by Japan, Korea was a tributary of the Qing Dynasty and, according to them, the Japanese colonization, though undoubtedly harsh, was better than the previous rule in terms of human rights and economic development.

They also argue that, the Kantogun (also known as the Kwantung Army) was at least partly culpable. Although the Kantogun was nominally subordinate to the Japanese high command at the time, its leadership demonstrated significant self-determination, as shown by its involvement in the plot to assassinate Zhang Zuolin in 1928, and the Manchurian Incident of 1931, which led to the foundation of Manchukuo in 1932. Moreover, at that time, it was the official policy of the Japanese high command to confine the conflict to Manchuria. But in defiance of the high command, the Kantogun invaded China proper, under the pretext of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. However, the Japanese government not only failed to court martial the officers responsible for these incidents, but it also accepted the war against China, and many of those who were involved were even promoted. (Some of the officers involved in the Nanking Massacre were also promoted.) Therefore, claims that the government was held hostage by soldiers on the field hold little weight.

Whether or not Hirohito himself bears any responsibility for such failures is a sticking point between the new right and new left. Officially, the imperial constitution, adopted under Emperor Meiji, gave full powers to the Emperor. Article 4 prescribed that “The Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the present Constitution” and article 11 prescribed that “The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and the Navy”.

For historian Akira Fujiwara, the thesis that the emperor as an organ of responsibility could not reverse cabinet decisions is a myth (shinwa) fabricated after the war. Others argue that Hirohito deliberately styled his rule in the manner of the British constitutional monarchy, and he always accepted the decisions and consensus reached by the high command. According to this position, the moral and political failure rests primarily with the Japanese High Command and the Cabinet, most of whom were later convicted at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal as class-A war criminals, apart all members of the imperial family such as prince Chichibu, prince Asaka, prince Higashikuni, prince Fushimi and prince Takeda.

Controversial reinterpretations outside Japan

Some activists outside Japan are also attempting controversial reinterpretations of Japanese imperialism. For example, the views of a South Korean ex-military officer and right wing commentator, Ji Man-Won, have caused controversy in Korea and further abroad. Ji has praised Japan for “modernising” Korea, and has said of women forced to become sex slaves: “most of the old women claiming to be former comfort women, or sex slaves to the Japanese military during World War II, are fakes.” In East Asia, such views are widely regarded as being offensive, libelous of the women concerned, and as representing historical revisionism just like how holocaust revisionists of Europe.

Later investigations

As with investigations of Nazi war criminals, official investigations and inquiries are still ongoing. During the 1990s, the South Korean government started investigating some individuals who had allegedly become wealthy while collaborating with the Japanese military. In South Korea, it is also alleged that, during the political climate of the Cold War, many such individuals and/or their associates or relatives were able to acquire influence with the wealth they had acquired collaborating with the Japanese and assisted in the covering-up, or non-investigation, of war crimes in order not to incriminate themselves. With the wealth they had amassed during the years of collaboration, they were able to further benefit their families by obtaining higher education for their relatives.

Non-government bodies and individuals have also undertaken their own investigations. For example, in 2005, a South Korean freelance journalist, Jung Soo-woong, located in Japan some descendants of people involved in the 1895 assassination of Empress Myeongseong (Queen Min), the last Empress of Korea. The assassination was conducted by the Dark Ocean Society, perhaps under the auspices of the Japanese government, because of the Empress’s involvement in attempts to reduce Japanese influence in Korea. Jung recorded the apologies of the individuals.

As these investigations continue more evidence is discovered each day. It has been claimed that the Japanese government intentionally destroyed the reports on Korean comfort women. Some have cited Japanese inventory logs and employee sheets on the battlefield as evidence for this claim. For example, one of the names on the list was of a comfort woman who stated she was forced to be a prostitute by the Japanese. She was classified as a nurse along with at least a dozen other verified comfort women who were not nurses or secretaries. Currently, the South Korean government is looking into the hundreds of other names on these lists.

Sensitive information regarding the Japanese occupation of Korea is often difficult to obtain. Many argue that this is due to the fact that the Government of Japan has gone out of its way to cover up many incidents that would otherwise lead to severe international criticism. On their part, Koreans have often expressed their abhorrence of Human experimentations carried out by the Imperial Japanese Army where people often became fodder as human test subjects in such macabre experiments as liquid nitrogen tests or biological weapons development programs Though some vivid and disturbing testimonies have survived, they are largely denied by the Japanese Government even to this day.

Source: Wikipedia

- The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific - June 7, 2023

- The D-Day Operation of June 6, 1944 - June 6, 2023

- The B-29 that Changed History - June 4, 2023