The Wayland Mayo Story

Biographical Notes

Aerial mapping pioneer, Ted Abrams, with his “Explorer,” the first aircraft designed exclusively for aerial photography, now in Smithsonian. Photo ca 1937 |

I was soon promoted to Photographic Supervisor which put me in charge of one of the largest labs in the U.S. I was also now in charge of five flight crews. They had several 180’s, a 185, and several AT-11’s. Ted Abrams is known as the father of aerial mapping. The Abrams Company is one of the largest mapping companies in the world. They had extremely large projects which kept the planes flying constantly. Some days it was not unusual to have five planes up.

Restored Abrams AT-ll at USAF Museum, WPAFB, OH. |

(My donations to the Air Force Museum consisted of many items such as silk escape maps, blood chits, many photos of the Yalu and the bridges, Antung Airfield in China, etc. Our crew dropped thousands of propaganda leaflets over enemy territory. These showed a picture of North Korean prisoners being well treated, smoking cigarettes. On the back was a ticket to surrender and be treated well. Many Chinese soldiers soon were running toward the American lines waving these tickets of surrender. I received a nice two page letter from the director of the museum thanking me for the donation, which was placed on display. He said he had not seen nor heard of these leaflets, up to that point in time.)

A typical job was one that took us to Albuquerque, N.M. to map the Rio Grande for the U.S. Government. We mapped many projects of over 4000 sq. miles. Many projects consisted of entire counties. I soon learned that the people operating the Stereo Plotters were making considerably more money than personnel in the photo lab. I learned to operate the plotter, they had 13, and soon transferred over to the Photogrammetric Dept. After being in Lansing for 7 years and freezing all the time I was thinking of moving.

The man who hired me at Abrams was Jack Freeman. He was moving up to take over the sales department and I took his old position. He quit in 1968 and started a new mapping company in Columbus, Ohio. One night I received a phone call. It was Jack Freeman, offering me a job in a company that had no employees. They did have a stereo plotter and Jack said I would be Chief Photogrammetrist, in charge of that section, the flight section (although it had no airplane), and the photo lab, which did not exist. I realize it was a questionable move, from a big established company to one where I would be the ONLY employee. I took the job.

|

We built a photo lab, from scratch. They bought a Zeiss camera. My friend Ray Lafferty owned a Cessna 195 so Jack subcontracted the flying to us. Yes, Ray let me fly his 195. It was a real handful to land with the spring-like gear, and when you flared out the nose came up and you couldn’t see. Anyway the company prospered and I was allowed to rent a Cessena 182 from Lane Aviation to go on business trips. I was finally in heaven, flying a 182 on my own on business trips, flying with Ray on mapping projects, and operating the stereo plotter. Business increased and pretty soon they had a complete photo lab, three stereo plotters, and a Cessena 206. I had more than I could handle. A pilot looking for a job to build time offered to work for $100 a week. I was back on the plotter full time and this pilot had never flown flight lines. I found myself having to go flying with him as he was having trouble finding and staying on the flight line. As things progressed, the company put in a complete drafting section, I brought in all my friends from Abrams. Soon they completed plans for a million dollar building. I guess I can take some of the credit for the company going from me, the only employee. to a large and very successful company.

|

||||||||

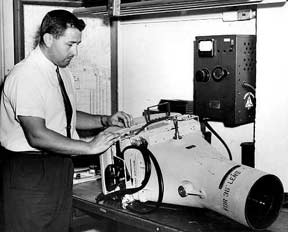

Wayland makes ready to leave from Fort Lauderdale for Dominican Republic in Cessena 206 in 1968 |

We did a lot of mapping in the Bahamas. Later, on a flight to La Romana in the Dominican Republic in the 206, I was delayed considerably by weather, with darkness approaching and low on gas. Rather than continuing on to Santo Domingo I decided cancel my flight plan and go directly to La Romana. Big mistake. La Romana at that time had only a very narrow and short dirt strip, with no communications. I had trouble locating the strip.

Finally I buzzed the area and soon saw two burning barrels, one at the beginning and one at the end of the runway. After a pretty rough landing I was met by several armed soldiers who placed me under arrest. I was there to work for the G&W Sugar Co., so the next day an exec from G&W explained everything and I was released.

End of Page 2 of Chapter 5 — Go to Chapter 6

Chapter — 01 — 02 — 03 — 04 — 05 — 06