A FINAL TRIBUTE TO PAUL

TIBBETS, PILOT OF ENOLA

- Page 4

Tibbets never regretted the bombing.

Finally, by early August,1945, the group was ready to undertake the still unknown mission. A group of seven B-29's was formed. Three weather planes would proceed ahead of the Enola , which would be accompanied by a photo plane, and one loaded with blast measuring instruments. Another plane would be used as a standby. August 6, 1945, was designated "drop day". The Enola had been loaded with the 9000 pound "Little Boy" which possessed the power of 15,000 tons of TNT. The Enola would not take off with the bomb armed, so Deak Parsons would arm the bomb in flight, a most risky procedure. After take off at 2:30AM they climbed to 30,700 feet. The weather planes which proceeded ahead of the Enola radioed that conditions over Hiroshima were acceptable, and Col. Tibbets gave his crew the word "It's Hiroshima". At 9:15 AM the Enola dropped the "Little Boy", and made her diving 155 degree turn to the right, and waited. The bomb exploded 1890 feet above the ground, with the mushroom cloud rising above 45,000 feet. The Japanese were given an ultimatum calling for an unconditional surrender, or face further attacks. Three days later the B-29 Bocks Car piloted by Chuck Sweeney dropped the second bomb the “Fat Man”on Nagasaki The unconditional surrender by the Japanese occurred on Aug 15, 1945.

FAT MAN NUCLEAR BOMB NMUSAF

THE ENOLA CONTROVERSY

Public sentiment over the atomic bombing of Japan fluctuated, as many felt we were the aggressors that bombed the innocent Japanese. The media had a field day, and was partially responsible for the turnaround in feelings. People seemed to forget the attack on Pearl Harbor. They forgot about the fanatical resistance at Iwo Jima, the Kamikaze attacks from Okinawa. They forgot the brutalization of our POW's, the numerous beheadings, the Bataan Death March. There seemed to be an emphasis on Japanese suffering, once again portraying the Americans as not really needing to drop the bomb. Why was there such an inbalance of public opinion? Was it politically motivated,or were we experiencing the Vietnam syndrome? Was it just the period of time that was changing Americans, and the rest of the world? The question persisted. Was it really necessary to drop the bomb? The very decision was now being questioned. This type of controversial thinking eventually worked it's way around to the Smithsonian bureaucracy, and the Enola became the focal point of all the dissention.

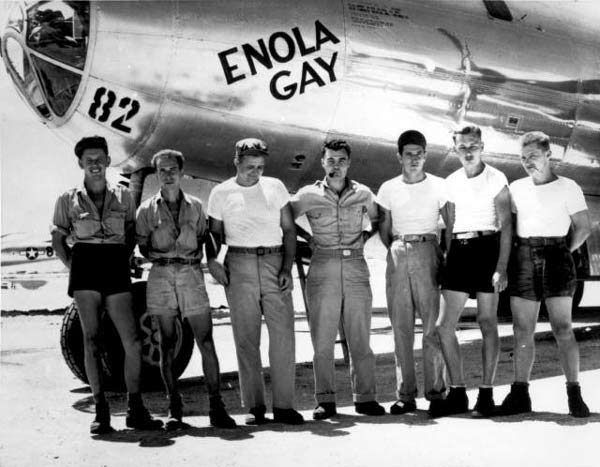

TIBBETS AND CREW

Several months after dropping the bomb the Enola was flown back to the United States. On Aug. 30, 1946, it was placed in storage and dropped from inventory. Three years later it was removed from storage and turned over to the Smithsonian for restoration and display. Little did we know what dissention and incompetence lay ahead for this "display". Apparently the Smithsonian, much to the dismay of thousands of veterans, allowed the plane to sit in storage for another 12 years. It was disassembled in 1961 and restoration not started until 1984. It would be another 11 years before it was finally put on display. During all these years the controversy raged, as WWII veterans groups voiced their objections not only to the Smithsonian handling of the project, but to the proposed manner they planned to portray the Enola . In April, 1994, the Air Force Magazine published an article which finally raised questions as to the Smithsonians intentions. Veterans rallied upon publication of this long overdue article and bombarded Congress with complaints. Apparently the Smithsonian was slanting the presentation to appear that the Japanese were the victims of a cruel American aggression. Photographs planned for the display were disproportionately sympathetic to the Japanese casualties and suffering, showing only a few American casualty photos. They planned a very emotional display showing the extreme suffering of the Japanese people. The wording was being twisted around to show the Americans bombed the Japanese as an act of vengeance and revenge. In reality they were rewriting history. Attacks on the Smithsonian were heating up, and Dr. Martin Harwit, director of the National Air and Space Museum, was on the receiving end of most of the flak. The Air Force Association and the Air Force Magazine were formidable opponents, with thousands of veterans and now Congress backing them up. The Smithsonian was questioning the morality of dropping the bomb, even suggesting maybe we should have invaded instead. Partitions of protest with thousands of signatures poured into the Smithsonian.